You or someone you love has just been diagnosed with cancer. You’ve met with the doctor and your head is spinning. You’re overwhelmed and scared.

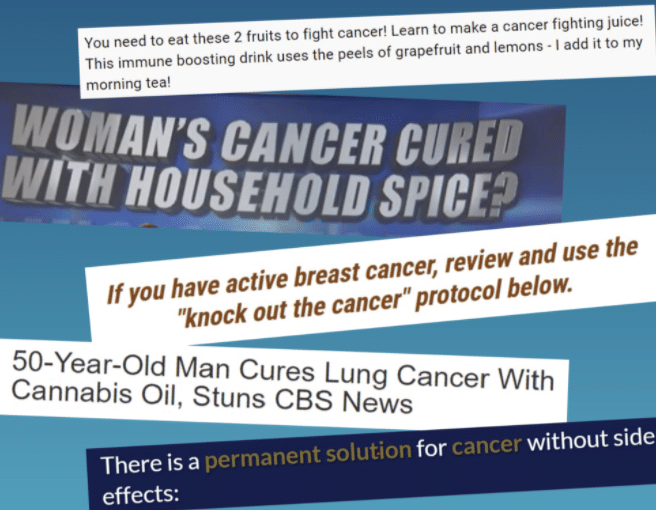

Like many people these days, you turn to the internet and social media for information. Someone you know points you to a scientific-sounding article or a video by a “medical expert” that offers new hope, perhaps by describing treatments that are “all natural” and don’t have unpleasant or serious side effects.

And although the information may sound too good to be true, the site includes testimonials from patients or their family members who describe miraculous results.

Scenarios like this are all too common, say oncologists, health communication experts, and the information specialists who field questions for NCI’s free Cancer Information Service (CIS).

“People have been sharing inaccurate health information since the beginning of time,” said Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou, Ph.D., M.P.H., of NCI’s Health Communication and Informatics Research Branch (HCIRB). But the internet and social media have made it far easier to share and spread health misinformation, Dr. Chou said.

Indeed, a recent study found that of the most popular articles posted on social media in 2018 and 2019 on the four most common cancers, one in every three contained false, inaccurate, or misleading information. And most of that misinformation about cancer was potentially harmful—for example, by promoting unproven treatments as alternatives to those that rigorous studies have shown to be beneficial, said Skyler Johnson, M.D., of the Huntsman Cancer Institute, who led the new study.

Further, Dr. Johnson’s team found, people were more likely to engage with misinformation than with factual information. A 2019 study of information about prostate cancer on YouTube reached similar conclusions.

“A substantial proportion of the content on YouTube was potentially biased and/or misinformative,” and those videos got more views and thumbs-ups than videos containing accurate information, said Stacy Loeb, M.D., M.Sc., of the NYU School of Medicine, who led that study.

For example, one popular video recommended injecting herbs into the prostate to treat cancer, which is unproven and potentially dangerous. More recently, other studies led by Dr. Loeb found similarly misleading information about prostate cancer on TikTok and Instagram.

“It’s clear that cancer misinformation is a pervasive problem across social networks,” Dr. Loeb continued. More research is needed on the impact of online misinformation on decisions about medical care and on people’s health, she added. And effective strategies are needed to address the problem, she stressed.

Solutions to this problem aren’t simple. But, according to several oncologists and health communication experts, health care providers can help by keeping the lines of communication open, listening to patients in a nonjudgmental way, working with them as partners to make decisions about cancer screening and treatment, and providing them with suggested resources for more information.

There’s growing evidence that cancer misinformation, particularly the promotion of unproven treatments, can be harmful.

A study published by Dr. Johnson and his colleagues in 2017, for example, found that people with cancer who had used alternative or complementary treatments instead of conventional cancer care had a greater risk of dying than people who received conventional cancer therapyExit Disclaimer.

However, this study did not look specifically at whether social media played a role in people’s decisions to use those treatments.

So in their new study, Dr. Johnson’s team examined 200 of the most popular articles about breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer shared on social media. The articles—50 on each cancer type—came from both traditional and nontraditional news outlets, personal blogs, crowdfunding sites, and other sources and were shared on Facebook, Reddit, Twitter, or Pinterest.

Two experts on each cancer type reviewed the articles in their field. They judged that 77% of articles containing misinformation included information that was probably or certainly harmful. Potential harms included dangerous effects of a suggested treatment, delaying or not seeking medical attention for a treatable or curable condition, and financial harm, including wasted money.

For example, one commonly shared story with potentially harmful misinformation claimed that ingesting cannabis oil can cure metastatic lung cancer or aggressive breast cancer.

“This study is noteworthy because it used an independent panel of experts and tried to quantify the extent of inaccurate or false information as well as the potential for causing harm,” said Dr. Chou. “It shows that exposure to cancer misinformation on social media is a reason for concern and something we need to investigate in more detail,” she continued.

For instance, someone at increased risk of cancer because of a family history may react differently to a health message than another person who is undergoing active treatment for an aggressive cancer. It will be important to study different groups of people to determine “whether or not certain messages that contain misinformation are more likely to resonate with them depending on their personal cancer situation,” said HCIRB chief Robin Vanderpool, Dr.P.H.

It’s also important to look at how people who are not experts evaluate specific claims on social media, Dr. Vanderpool said. Video, tone of voice, and even things such as color schemes can have a strong impact on how people process information, she noted.

“We’re now doing a deep dive to identify specific features of an article that are predictors of misinformation and harm,” such as where the article appeared, who wrote it, and the types of claims being made, Dr. Johnson said. His team is also doing follow-up studies to find out how people with cancer decide if an article is accurate, and to identify groups of people that are more susceptible to misinformation.

Ultimately, he said, they hope to develop ways “to help patients overcome misinformation that they encounter.”

Doctors who diagnose and treat cancer have been dealing with misinformation for a long time. And some misinformation can lead patients to express doubts, hesitancy, or fear of taking proven treatments, said Lidia Schapira, M.D., of Stanford University, an oncologist who specializes in treating breast cancer. In these situations, listening to people’s concerns with empathy and respect is critical, she emphasized.

Dr. Schapira starts “by asking questions, listening, and being nonjudgmental.” From there, she tries to identify opportunities for negotiation. “For example, I will ask the patient to imagine the consequences of taking or not taking such a treatment, and then try to find some alignment of purpose—such as achieving a cure or good quality of life—and common ground.”

These conversations are “all goal oriented, with the goal being what’s best for the patient,” she continued. And often, she said, multiple conversations are needed.

Dr. Johnson, a radiation oncologist, encourages his patients to talk with him about cancer information they may have come across on social media. Doctors “should be aware that misinformation is out there and let patients know they should feel free to discuss it with their health care providers,” he said.

“It’s very important to have an open discussion with people about what they’ve seen on social media, and to share evidence-based cancer information on what is recommended in their case,” Dr. Loeb agreed.

Organizations like NCI and the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which provide expert-reviewed information about cancer for patients and families, can help counter misinformation by serving as a trusted source of science-based information, Dr. Schapira said. Many patient advocacy groups also provide reliable cancer information that is expert reviewed, she said.

“One of the main benefits of providing and having access to good information rather than misinformation is that the patient and family are empowered to have a better discussion” with their doctors, Dr. Schapira noted.

Ideally, Dr. Loeb said, doctors and patients should work together to make decisions about cancer care.

That includes “discussing the benefits, risks, and alternatives for a given procedure or treatment, as well as discussing the patient’s preferences,” she said. Such an approach, known as shared decision making, is especially important “in situations where there are multiple options and it’s not known what the best option is,” Dr. Loeb noted.

People who provide cancer information for the public echoed many of these themes.

“We get a lot of questions from people with advanced cancer who are looking for things other than standard treatment options,” said Cancer Information Service resource specialist Laura Rankin. They may have read about an unproven treatment such as an herbal remedy or high-dose vitamins online, or a friend or relative may have told them about it.

“They think that these are a sure-fire way to treat cancer … and don’t understand that what they’re asking about has no proof of being effective and could even be harmful,” Rankin said.

One important goal CIS has is “to help people understand how to evaluate whether information they find online is credible,” said Deborah Pearson, M.P.H., a former oncology nurse who helps oversee CIS. The Using Trusted Resources page on NCI’s website, which CIS helped develop, “gives people lots of criteria to use so they can be more informed consumers of information,” Rankin said.

When people contact CIS, “we try to understand where the person is coming from, what is motivating them. People may be desperate and vulnerable,” especially if they have limited treatment options, Pearson said.

In addition to providing information, CIS staff can help people brainstorm about how to talk with their doctor.

“If their oncologist is too busy, we ask if there is a nurse or a primary care doctor they could talk with,” said Lauren Tarry, a supervisor at CIS. “Some dietary supplements could interact with your treatment, so it’s always important to talk with your doctor” before taking something, she noted.

Having a health care provider whom you connect with and trust is important, Pearson said.

Social media can also be part of the remedy for cancer misinformation, Dr. Loeb said.

“It’s important for physicians and other experts to actively engage online to share evidence-based health information and ensure that the latest scientific findings are reaching the public through these large networks,” she said.

Dr. Loeb is active on Twitter and also works with professional societies and foundations in prioritizing, planning, and reviewing their social media content for patients. She started a Twitter-based journal club with the Prostate Cancer Foundation with the hashtag #ProstateJC, where scientists can discuss new research in that field.

And that has “helped foster scientific discussion about new research that is open to patients and the general public as well as international experts with a range of expertise,” she said.

In addition, Dr. Loeb noted, “all of the major medical conferences now have dedicated social media hashtags. Those are a great way for patients and the public to follow along with the latest research that’s being shared.”

Medical societies, journals, and organizations like NCI also are active on social media and are sources of reliable information.

Many questions remain about social media and cancer misinformation—not to mention misinformation on other health topics, such as COVID-19.

For instance, Dr. Vanderpool said, “We also need more studies on the health impacts of cancer misinformation through social media, such as not taking or completing your cancer treatment, parents forgoing human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for their children, or not getting screened for cancer.”

Learning the origins of misinformation on social media and the reasons behind sharing it are also critical for efforts to limit its spread, Dr. Chou said. For example, she said, “is there a profit motive or a group that’s trying to cause confusion or chaos?”

The ability to access health information online is important and empowering and helps patients be proactive in their own care, experts agreed. But because so much information is now available online, the burden of deciding what is true or false is increasingly falling on individual consumers, Dr. Chou said. Furthermore, she noted, “the algorithms developed and perpetuated by the social media platforms affect what each person is likely to see on social media.

“We need to combat misinformation in multiple ways, at multiple levels,” Dr. Chou continued.

Health care professionals, research and health care organizations, government agencies, and technology and social media companies all need to take responsibility and play a role in addressing the problem, she said. And to help individuals be more critical consumers of information, “we also need to think about education and health literacy opportunities, which could go into the K–12 and college curricula,” Dr. Chou said.

“We assume that if you give someone good information you can help and make a difference, but we need to acknowledge that we live in a very noisy environment,” she continued. “The floodgate has been opened and we have to work with that.”

Source: National Cancer Institute

Back to Latest news