Join over 1,000 people in helping the Paula Takacs Foundation raise crucial funds for groundbreaking research and clinical trials, all while spreading awareness to accelerate diagnoses and save lives.

“Unite for a Cure” Against Sarcoma

Join over 1,000 people in helping the Paula Takacs Foundation raise crucial funds for groundbreaking research and clinical trials, all while spreading awareness to accelerate diagnoses and save lives.

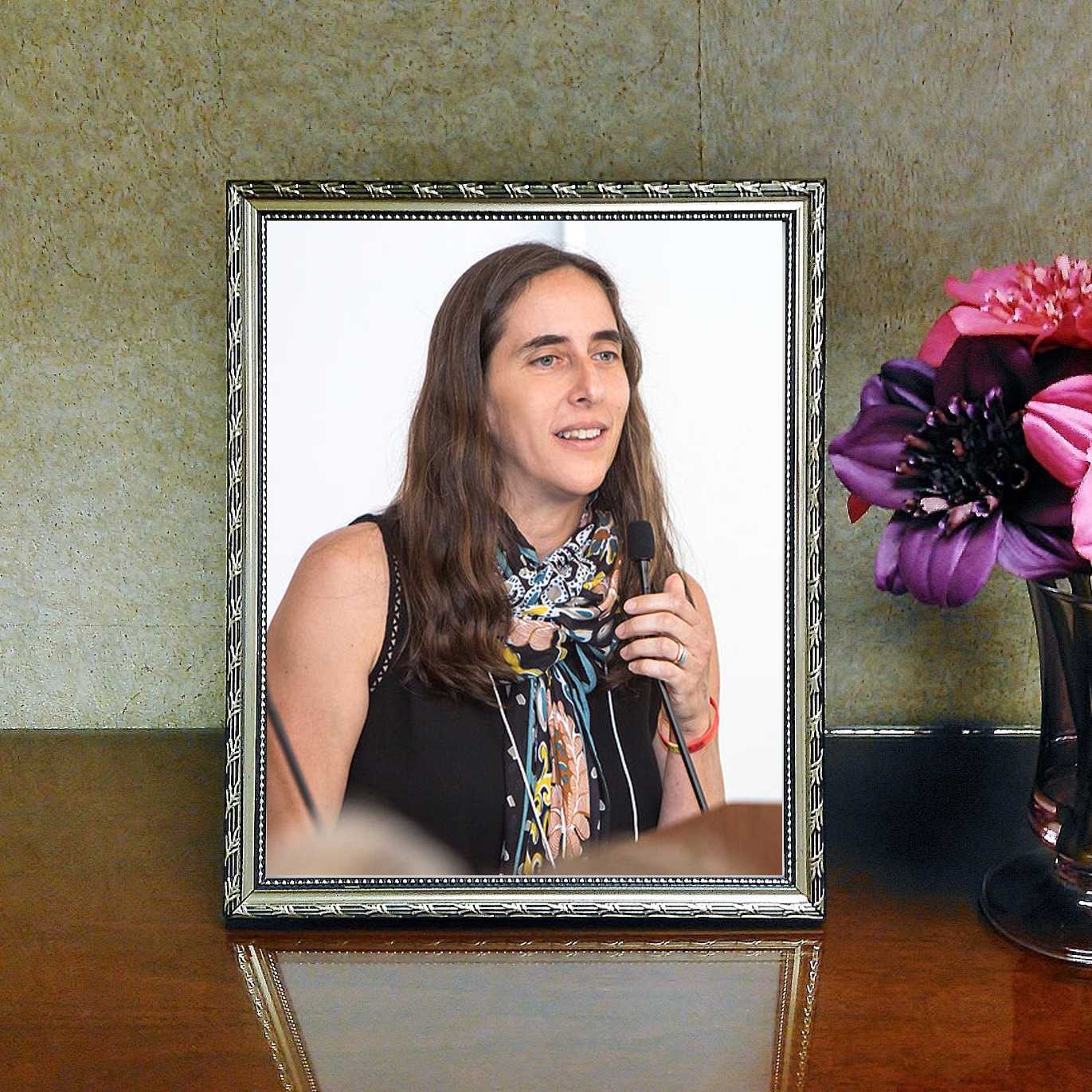

The Paula Takacs Foundation for Sarcoma Research is immensely proud to announce the establishment of the Paula Takacs Foundation Endowed Chair of Sarcoma Research at Levine Cancer Institute, supported by a $2 Million endowment fund.

We know Paula would be so proud, and maybe not even surprised, because it was her relentless commitment to her vision to change the outcome for sarcoma patients in Charlotte and around the world that catalyzed this historic announcement.

Take a few moments to watch Susan Udelson announce the endowment, and then read our Q&A to fully understand all facets of this monumental gift and its local and global impact on sarcoma research.

A: An Endowed Chair is one of the highest honors in academic medicine. These positions are often reserved for full professors who are perceived as being the best of the best in their area of expertise. There are few Endowed Chairs of Sarcoma Research in the U.S., and who receive this type and level of funding for sarcoma research.

A: At the heart of every great cancer center are scholars whose work is supported by endowed funds. Endowed Chairs create opportunities for these institutions to attract and retain distinguished professors who will significantly drive and impact a particular area of study and elevate the reputation of the organization itself. Endowed positions recognize outstanding faculty, acknowledge their professional standing and provide substantial support for the conduct of scholarly work and research.

A: A professor level faculty who is an expert in sarcoma research will receive this prestigious appointment by the President of Levine Cancer Institute and other Atrium Health leadership during a forthcoming announcement and investiture ceremony. Stay tuned to find out who Levine Cancer Institute names as the inaugural Paula Takacs Foundation Endowed Chair!

A: There are many! The Paula Takacs Foundation Endowed Chair will direct the use of this $2 million endowment. It is the Chair’s responsibility to use a portion of these special funds at their discretion, each and every year, to advance science in the most strategic and novel ways possible. The endowment will ensure Levine Cancer Institute’s dedicated focus on this disease for all eternity! For Paula’s family, it keeps her name and beautiful legacy growing stronger forever too! It also brings national exposure and recognition to the Levine Cancer Institute sarcoma research program and Paula Takacs Foundation, attracting additional sarcoma talent to our region and ultimately benefiting patients throughout the globe.

A: An endowment fund exists in perpetuity and is part of the long-term capital base of the cancer center. Earnings from the endowment are an ongoing source of support, despite fluctuations in the economy. A strong endowment allows the cancer center to plan for the future while continuing to drive innovation and research.

A: The $2 million Endowment has been funded to solely support research at Levine Cancer Institute, as envisioned by the Paula Takacs Foundation Endowed Chair and reviewed by the Endowment Committee. The Paula Takacs Sarcoma Research Fund continues to operate separately, supporting cutting-edge studies and clinical trials at Levine Cancer Institute and/or Levine Children’s Hospital at the direction of Fund’s Advisory Committee.

Want to keep up to date with all the latest sarcoma news, educational materials, foundation developments, and cancer resources? Sign up for our monthly newsletter.

Want to get involved in the work of our foundation? Here are some ways you can make a huge difference.

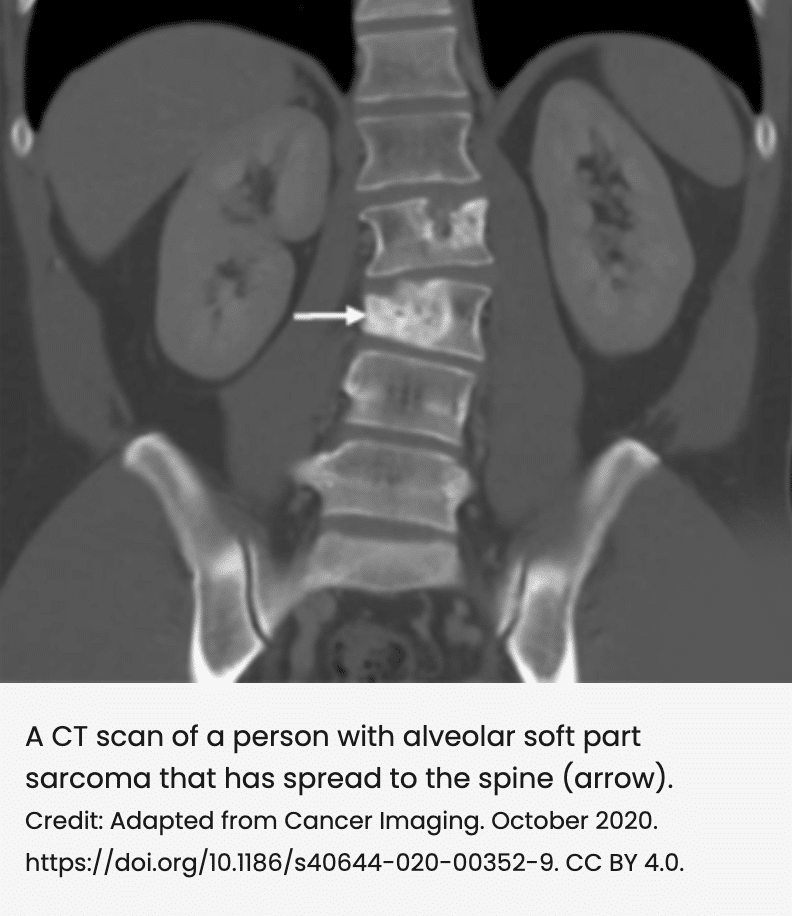

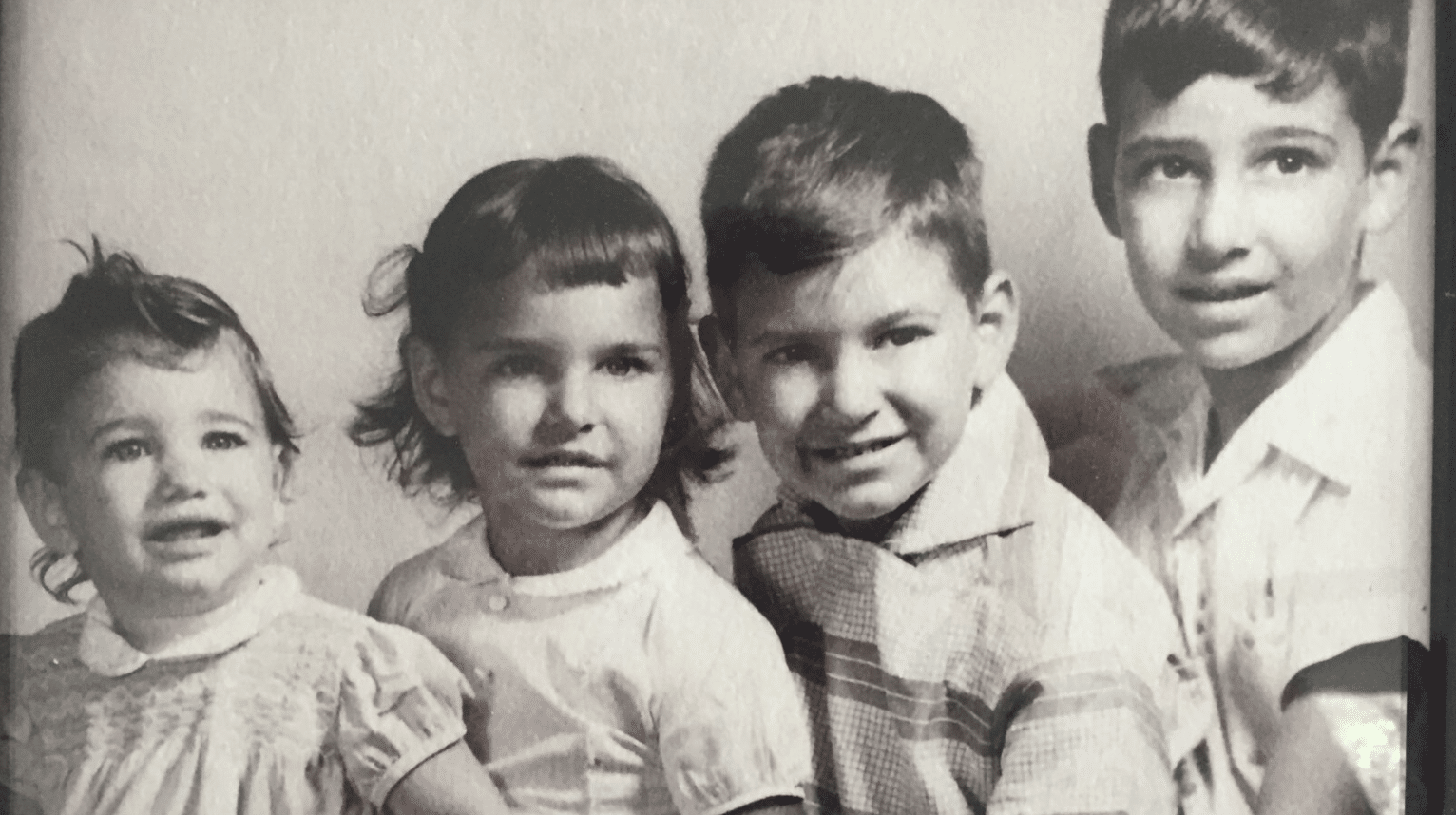

Faithanne Hill was only 11 when she was diagnosed with alveolar soft part sarcoma, an extremely rare soft tissue cancer that is diagnosed in only about 80 people (mostly adolescents and young adults) in the United States each year. Now 21, the first-year college student has been through a lot over the past decade.

In addition to going through the usual teenage experiences in her home country of Trinidad, she’s also had a half dozen or so surgeries at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD, to remove new tumors that seemed to develop out of nowhere—a common occurrence for this cancer.

So far, the surgeries have kept her disease at bay. But Faithanne said she worries that, one day, surgery won’t work anymore, and she will have few treatment options. Chemotherapy generally doesn’t work for alveolar soft part sarcoma.

Several years ago, Faithanne joined a clinical trial to see whether the immunotherapy drug atezolizumab (Tecentriq) could help shrink her tumors. Results of that study, which included 52 people with advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma, were published September 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

All 52 people in the trial were treated with atezolizumab. Of these, 19 (37%) saw their tumors shrink by at least 30% (partial response), and one person’s tumors disappeared altogether (complete response). Patients who were treated for more than 2 years were given the option to take a treatment break.

Seven patients chose this option and, so far, none have had evidence on imaging scans that their tumors are growing again.

In December 2022, based on an earlier review of this study and its findings, the Food and Drug Administration approved atezolizumab for adults and children 2 years and older with advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma. This is the first drug ever approved for this rare disease.

“What this trial has shown is that you can manage alveolar soft part sarcoma by managing the immune system,” said Alice Chen, M.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis (DCTD), who led the study. “It’s also possible that patients may be able to stop treatment after a period of time. For these young people, that may make a huge difference.”

“This study is a tour de force,” said Christian F. Meyer, M.D., Ph.D., a sarcoma specialist at Johns Hopkins Medicine, who was not part of the trial. “Eight years ago, we were not thinking about immune therapies for alveolar soft part sarcoma, and here we are now with a drug approval based largely on this work. This study also provides hope that trials in rare cancers are possible and can lead to really pivotal results.”

Although Faithanne had to leave the trial early to undergo a major surgery for her cancer, she said she’s relieved that there is now an approved treatment if her cancer progresses.

“I’m really happy that they’ve found something that works,” she said.

Alveolar soft part sarcoma, or ASPS, is a type of soft-tissue sarcoma that can form in muscle, bone, nerves, and fat. ASPS grows more slowly than many other sarcomas and generally develops in younger people.

It often starts as a painless lump in the leg, arm, head, or neck but can spread to other parts of the body, such as the lungs. It can also spread to the brain, which is not often seen with other soft tissue sarcomas.

Patients usually have surgery to remove ASPS tumors, often followed by radiation to kill any remaining cancer cells. But the tumors often come back, requiring many subsequent surgeries.

Once the disease spreads beyond where it originally developed, and if the disease spreads to locations where it cannot be surgically removed, there has been no effective treatment for the disease. Less than 50% of people with ASPS that has spread and cannot be treated surgically survive 5 years after diagnosis.

With chemotherapy largely ineffective against ASPS, researchers have been exploring newer treatments, including targeted therapies, but with little success. One targeted therapy, pazopanib (Votrient), has been approved for soft tissue sarcomas in general, but it’s unclear how well it works against ASPS.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as atezolizumab have also shown hints of promise. In a small clinical trialExit Disclaimer, tumors shrank in 6 of 11 people with ASPS treated with a combination of the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and the targeted drug axitinib (Inlyta).

Atezolizumab, which is approved to treat several other types of cancer, had also shown some effectiveness, anecdotally, in several people with this cancer.

Based on these anecdotal findings, Dr. Chen and her colleagues at NCI wanted to see whether they could achieve similar results under the more rigorous standards of a clinical trial. Genentech, which manufactures atezolizumab, provided the drug for the trial under a special research agreement with NCI.

In the phase 2 trial, 52 adults and children with advanced ASPS who had not previously been treated with checkpoint inhibitors were given an infusion of atezolizumab every 21 days.

Among the 37% of participants whose tumors responded to the treatment, the lone complete response occurred about a year after the person began treatment. Of the remaining 33 participants, 30 had stable disease—that is, their cancer didn’t get better or worse. Typically, without treatment, ASPS tumors will continue to grow, Dr. Chen said.

Most people who responded to treatment began to see tumor shrinkage within the first 3 to 5 months. For three patients, it took more than a year of atezolizumab infusions before their tumors began to shrink.

Side effects of the treatment were mostly mild and included anemia, diarrhea, rash, and pain. Nobody discontinued treatment because of side effects.

After more than 2 years of treatment, seven people opted to take a 2-year break from treatment. Two of the 7 have completed the break without needing to resume atezolizumab at any point, so they have left the study.

The five others are still completing their treatment break. So far, none of the 7 patients have experienced a progression or return of their cancer.

Elad Sharon, M.D., of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, who co-led the study while he was at NCI, pointed out that atezolizumab has not been shown to be as effective in other sarcomas as it is for ASPS.

Designing and running a clinical trial requires the skills of many experts. Each team may be set up differently at different sites. Typical team members and their duties include:

Principal investigator – supervises all aspects of a clinical trial. This person:

Research nurse – manages the collection of data throughout the course of a clinical trial. This person:

Data manager – manages the collection of data throughout the course of a clinical trial. This person:

Staff physician or nurse – helps take care of the patients during a clinical trial. This person:

LAS VEGAS, May 10, 2023 /PRNewswire/ — DelveInsight’s ‘Soft Tissue Sarcoma Pipeline Insight – 2023‘ report provides comprehensive global coverage of available, marketed, and pipeline soft tissue sarcoma therapies in various stages of clinical development, major pharmaceutical companies are working to advance the pipeline space and future growth potential of the soft tissue sarcoma pipeline domain.

Request a sample and discover the recent advances in soft tissue sarcoma drug treatment @ Soft Tissue Sarcoma Pipeline Report

The soft tissue sarcoma pipeline report provides detailed profiles of pipeline assets, a comparative analysis of clinical and non-clinical stage soft tissue sarcoma drugs, inactive and dormant assets, a comprehensive assessment of driving and restraining factors, and an assessment of opportunities and risks in the soft tissue sarcoma clinical trial landscape.

Soft-tissue sarcomas (STS) are rare neoplasms that can develop in supporting or connective tissue, such as muscle, nerves, tendons, blood vessels, and fatty and fibrous tissues. They commonly affect the arms, legs, and trunk. They can also be found in the stomach and intestines (GIST), behind the abdomen (retroperitoneal sarcomas), and in the female reproductive system (gynecological sarcomas). Soft tissue sarcomas are classified based on the cell type involved, the nature of the malignancy, and the clinical course of the disease.

The signs and soft tissue sarcoma symptoms differ greatly between patients depending on the type of soft tissue sarcoma. It is not associated with any obvious symptoms early in the course of the disease, but affected individuals may notice a slow-growing, painless mass in the affected area.

Find out more about drugs for soft tissue sarcoma @ New Soft Tissue Sarcoma Drugs

Learn more about the emerging soft tissue sarcoma pipeline therapies @ Soft Tissue Sarcoma Clinical Trials

Dive deep into rich insights for new drugs for soft tissue sarcoma treatment; visit @ Soft Tissue Sarcoma Medications

For further information on the soft tissue sarcoma pipeline therapeutics, reach out @ Soft Tissue Sarcoma Drug Treatment

Related Reports

Soft Tissue Sarcoma Market Insights, Epidemiology, and Market Forecast – 2032 report deliver an in-depth understanding of the disease, historical and forecasted epidemiology, market share of the individual therapies, and key soft tissue sarcoma companies, including Gem Pharmaceuticals, Lytix Biopharma, Incyte Corporation, Daiichi Sankyo, NantPharma, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Agenus, Eli Lilly and Company, Adaptimmune, Aadi, AVEO Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, among others.

Soft Tissue Sarcoma Epidemiology Forecast

Soft Tissue Sarcoma Epidemiology Forecast – 2032 report delivers an in-depth understanding of the disease, historical and forecasted epidemiology, as well as the soft tissue sarcoma epidemiology trends.

Clear Cell Sarcoma Pipeline Insight – 2023 report provides comprehensive insights about the pipeline landscape, including clinical and non-clinical stage products and the key clear cell sarcoma companies, including Tesaro, NantPharma, Rafael Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, among others.

Ewing Sarcoma Pipeline Insight – 2023 report provides comprehensive insights about the pipeline landscape, including clinical and non-clinical stage products, and the key Ewing sarcoma companies, including Gradalis, Inc., Shanghai Pharmaceuticals Holding Co., Ltd, Tyme, Inc, Pfizer, Hutchison Medipharma Limited, among others.

About DelveInsight

DelveInsight is a leading Business Consultant and Market Research firm focused exclusively on life sciences. It supports pharma companies by providing comprehensive end-to-end solutions to improve their performance. Get hassle-free access to all the healthcare and pharma market research reports through our subscription-based platform PharmDelve.

Contact Us

Shruti Thakur

info@delveinsight.com

+1(919)321-6187

www.delveinsight.com

Logo: https://mma.prnewswire.com/media/1082265/DelveInsight_Logo.jpg

SOURCE: PRNewswire

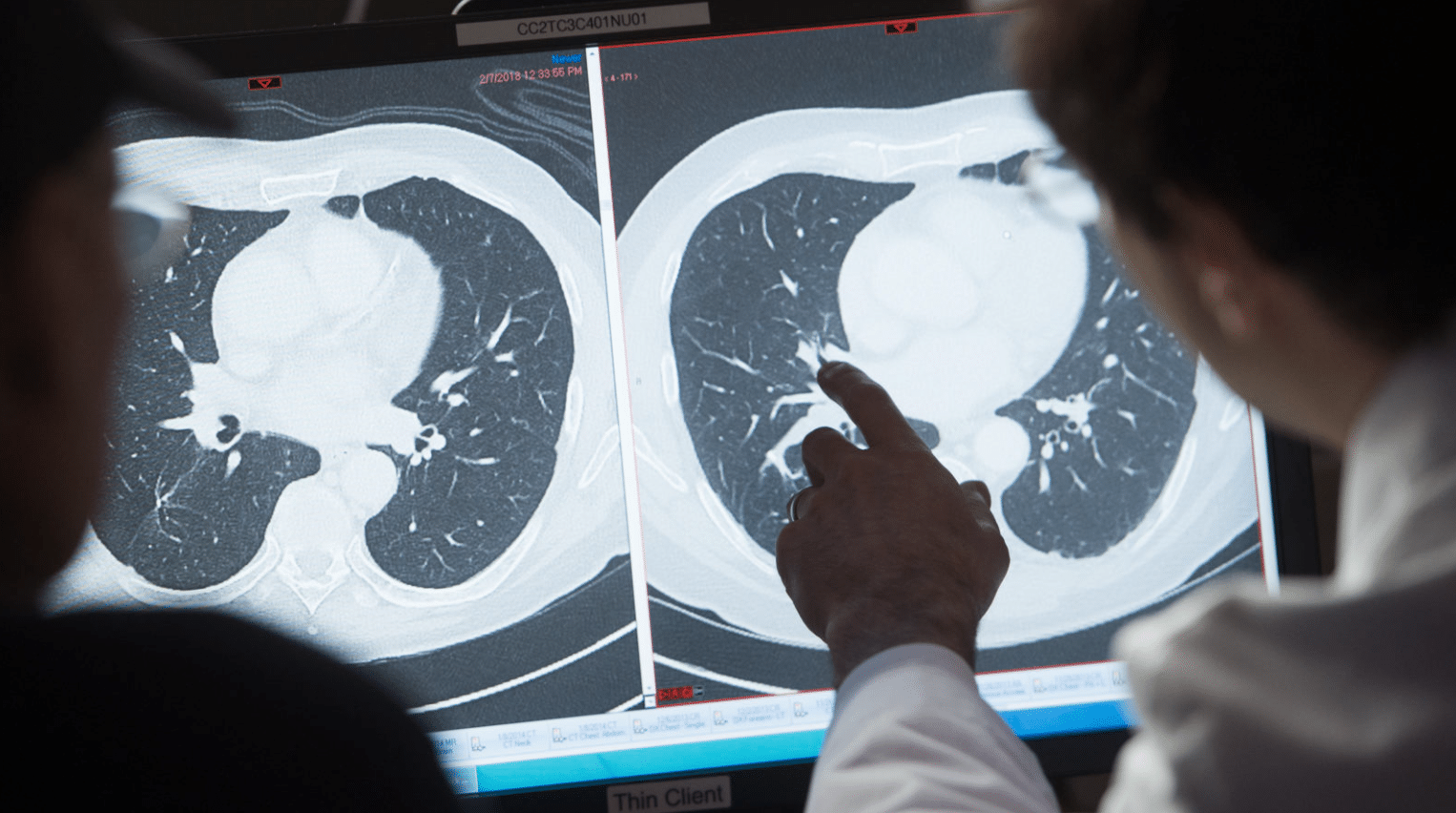

Cancer researchers continue to make progress in developing tests using liquid biopsies that could complement and even serve as an alternative to traditional tissue biopsies. These tests, which analyze bits of free-floating genetic and other material shed by tumors into the blood and other body fluids, are already being used to detect cancer-related genetic changes and guide treatment decisions.

Until recently, much of the research on liquid biopsies focused on their use in adults with cancer. But scientists have begun to make progress in developing liquid biopsy tests specifically for use in children with cancer, including those with solid cancers like Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, and Wilms tumor, a type of kidney cancer.

A recently published study by researchers at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) and the University of Southern California describes the use of one such liquid biopsy approach.

The test, which analyzes bits of DNA in samples of blood, showed promise in diagnosing various types of solid tumors in childrenExit Disclaimer, the team reported February 20 in npj Precision Oncology. It also showed potential for determining whether a tumor is responding to treatment or may be coming back after initial successful treatment.

“It’s a very well done, interesting study and adds a lot of data to the field,” said Mark Applebaum, M.D., a pediatrics researcher at the University of Chicago, who noted that other teams have developed similar approaches. Dr. Applebaum also works in this area but was not involved in the new study.

Liquid biopsies are of particular interest for use in children because they are less invasive and easier to repeat than tissue biopsies, said Jaclyn Biegel, Ph.D., director of the Center for Personalized Medicine at CHLA, who co-led the new study.

The new findings provide “proof of principle” that the test could be useful in the clinic, said Brian Sorg, Ph.D., a program director in NCI’s Cancer Diagnosis Program, who also was not involved in the study.

Accurately diagnosing cancer in children can be difficult because children can develop a wide range of solid tumors in different parts of the body. And each tumor type often has multiple subtypes with different features that can affect a patient’s prognosis and treatment, said Miguel Ossandon, Ph.D., also of NCI’s Cancer Diagnosis Program.

A tissue biopsy, in which a sample of tumor is removed with a large needle or during surgery, is still the gold standard for diagnosis, Dr. Ossandon said. “But tissue biopsy has limitations, and some of those limitations can be overcome with a liquid biopsy.”

Some liquid biopsies developed for use in adults with cancer have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to help guide treatment decisions. But liquid biopsies developed for adults can’t be used for children with cancer.

That’s because “the tumor types you see in children are very different from what you see in adults—the tumors are driven by different genomic [changes],” Dr. Biegel said.

In addition, she said, pediatric liquid biopsies must work with smaller samples of blood or other body fluids.

The liquid biopsy approach that Dr. Biegel and her colleagues developed “is geared towards using very small amounts of DNA” in blood and other body fluids to look for genetic changes typically found in pediatric cancers, she said.

Cancer in adults often results from small changes, or mutations, in one or a few letters (nucleotides) of the DNA code in cells. But solid cancers in children are often caused by changes in the structure of chromosomes in cells, Dr. Biegel explained.

These changes can include the disappearance or duplication of one or more genes in a chromosome, known as copy number alterations. Another common change is a gene fusion, which can result when part of the DNA from one chromosome moves to another chromosome, joining parts of two different genes.

The liquid biopsy test looks for copy number alterations using a technique called low-pass whole-genome sequencing. This method, which can be applied to many samples simultaneously at relatively low cost, can also detect some but not all single-nucleotide changes.

And whereas many liquid biopsies being developed for use in children are designed to detect a single type of cancer, the CHLA and USC team’s approach, as well as similar tests being developed by other researchers, is designed to detect multiple cancer types.

To evaluate whether their low-pass whole-genome sequencing method could identify the presence of cancer in children known to have the disease and distinguish those with cancer from those without cancer, the team analyzed blood samples from 73 patients with a variety of solid cancers and 19 patients who did not have cancer (controls).

Patients ranged in age from 6 months to 28 years. All cancer patients in the study had a diagnosis that was previously confirmed using established testing methods.

The test successfully detected copy number alterations in DNA from the blood of patients with a range of pediatric solid cancer types, including in 26 of 37 newly diagnosed patients (70%). Of those patients, 27 had localized cancer—that is, the cancer had not spread beyond its original location in the body—and copy number alterations were found in 18 (67%) of them.

The ability to detect copy number alterations in samples from children with localized cancer is noteworthy, Dr. Biegel and her team wrote, because the levels of tumor DNA circulating in blood tend to be lower in patients with localized (earlier-stage) disease.

Of the 19 patients who did not have cancer, 16 did not have detectable copy number alterations. The other three had hereditary losses of a portion of one chromosome that were not related to cancer and were therefore dropped from further analysis.

Next, the team looked at whether their test could detect specific patterns of copy number alterations that are linked with individual cancer types. The test’s ability to do so, they reported, varied depending on the type of cancer.

The researchers also wanted to see if the test has potential to track how childrens’ cancers are responding to treatment or enable earlier detection of cancer that has come back (recurred) after treatment is completed. So, using blood samples taken from patients at different times after treatment, they looked for changes in the levels and patterns of copy number alterations.

In some children, copy number alterations could no longer be detected following treatment, suggesting that the test could be used to monitor patients’ responses to treatment. And in one patient with advanced osteosarcoma, the test detected copy number alterations in blood samples—indicating that the cancer had come back—taken 9 months before imaging tests had shown a recurrence of the cancer.

Since completing this study, Dr. Biegel said that after additional testing, her team has begun using their test for copy number alterations as part of patient care at CHLA and “it’s been extremely helpful,” she said.

For instance, in one patient they used the liquid biopsy to distinguish between two types of childhood liver cancer, hepatoblastoma and a rare cancer called embryonal sarcoma of the liver, that have very different treatments and outlooks.

The team also used the test in samples of cerebrospinal fluid (fluid that circulates around the brain) from some children with brain cancer to help identify cancer that remained after treatment when imaging tests were inconclusive, Dr. Biegel said.

The next version of the liquid biopsy test will also look for individual mutations and gene fusions that are well-established markers of certain pediatric cancers using a method known as targeted sequencing. In contrast to low-pass whole-genome sequencing, this method is a deeper dive into one specific region of the genome and more reliably detects these types of genetic changes.

To see if they could detect these changes with a liquid biopsy as effectively as they could using tumor samples, the researchers tested their targeted sequencing approach on blood samples from children with Ewing sarcoma or alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. They were able to detect cancer-related gene fusions in most patients, including some who did not have detectable copy number alterations.

Both the low-pass whole-genome sequencing and targeted sequencing tests can be done at the same time on a single small sample of blood or other body fluid, Dr. Biegel said.

And, Drs. Ossandon and Sorg said, combining these two tests could improve the performance of the liquid biopsy for detecting and diagnosing childhood cancers.

However, further studies are needed to figure out exactly how and in what cases the combination of these two types of genetic analysis will be most useful, Dr. Biegel said.

She also noted that their liquid biopsy method is not intended as a standalone test but is meant to be combined with other diagnostic methods, such as imaging, when a tissue biopsy is not feasible.

Indeed, like other diagnostic tests, liquid biopsies have both advantages and disadvantages. For instance, Dr. Sorg said, a liquid biopsy can capture genetic material shed by tumors throughout the body, whereas a tissue biopsy “only tells you about the portion of the specific tumor that you’re sampling.”

On the other hand, he continued, a liquid biopsy “doesn’t tell you anything about where the tumors are located,” but that information can usually be obtained with imaging tests.

Before the new test is ready for wider use, Dr. Ossandon said, it will need to be validated in more patients, including children who do not yet have a definitive cancer diagnosis. In addition, he said, clinical trials that follow patients over time will be needed to find out if this and other pediatric liquid biopsy approaches can be used to monitor cancer effectively or provide accurate information on a patient’s prognosis.

“Using low-pass whole-genome sequencing to detect copy number aberrations and [look at] patterns of change over time is a very feasible and doable concept,” Dr. Applebaum said.

“However, we’re still trying to figure out how to use it to guide therapy.”

(SACRAMENTO)In a significant new study, UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center researchers have uncovered a link between a patient’s microbiome and their immune system that can potentially be used to improve the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma. This type of cancer is found in connective tissues like muscle, fat and nerves.

Findings from the study were published in the Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

“The study’s data show new lines of research in the paradigm-shifting concept that the microbiome of a patient and their immune system can interact and shape one another, as well as be potentially engineered to improve patient outcomes,” said Robert Canter, the lead author of the study and chief of the Division of Surgical Oncology.

The gut microbiome is made of microorganisms in the digestive tract that include bacteria, fungi and viruses. Microbial communities have also been found in other parts of the body, including the mouth, lungs and skin. And now the study shows they are also found in tumor cells.

“We found that soft tissue sarcomas harbor a quantifiable amount of microbiome within the tumor environment. Most importantly, we found that the amount of microbiome at diagnosis may be linked with the patient’s prognosis,” Canter added.

Although the levels of microbes are low, the study findings are significant because many tumors, especially sarcomas, were believed to be sterile.

“We found that soft tissue sarcomas harbor a quantifiable amount of microbiome within the tumor environment. Most importantly, we found that the amount of microbiome at diagnosis may be linked with the patient’s prognosis.”—Robert Canter, chief, UC Davis Division of Surgical Oncology

The UC Davis researchers also uncovered how the microbiome within a sarcoma tumor plays a role in attracting specific types of immune cells like cancer-fighting natural killer cells. Canter said that’s important because the higher the rate of natural killer cell infiltration in a tumor, the greater the chance that the sarcoma won’t spread to other parts of the body. Natural killer cells are a prime target for improving the effectiveness of immunotherapy.

The team found that viruses within the microbiome of a tumor appear to impact the amount of natural killer cells found in sarcomas and, for that reason, affect survival rates. Specifically, the study found a strong positive correlation between the presence of Respirovirus, a genre of viruses known for causing respiratory illnesses, and the presence of natural killer cells in the tumor. Canter and his colleagues are now considering ways to create viruses to attract more cancer-killing immune cells.

“It has become clear that the microbiome in the gut and other parts of the body has a major impact on human health and disease. Amazingly, it shapes the immune system throughout the body and, because of its interaction with the immune system, we now know it also has a big role in how the body responds to cancer and cancer treatments like immunotherapy,” Canter said.

The authors obtained tumor and stool samples from 15 adult patients with non-metastatic soft tissue sarcoma, which was studied for a median of 24 months. Analysis revealed that most of the tumors were advanced stage III (87%) and affected a patient’s limb (67%).

Tissue samples were sent to the university’s Genome Center in Davis for sequencing and to the Flow Cytometry Shared Resource Laboratory on the UC Davis medical campus in Sacramento for immune profiling. Patients were monitored for two years as part of their cancer treatment follow-up.

Canter said past research has shown the existence of microbiome inside tumors across several cancer types, including breast, lung, pancreas and melanoma. For that reason, he said further research into the connection between microbiome and the immune system in other cancer types is warranted.

Coauthors on the study are Lauren Perry, Sylvia Cruz, Kara Kleber, Sean Judge, Morgan Darrow, Louis Jones, Ugur Basmaci, Nikhil Joshi, Matthew Settles, Blythe Durbin-Johnson, Alicia Gingrich, Arta Monjazeb, Janai Carr-Ascher, Steven Thorpe, William Murphy, and Jonathan Eisen.

This work was supported by the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center and the UC Davis Flow Cytometry Shared Resource Laboratory, with funding from National Cancer Institute grants P30 CA093373, S10 OD018223 and S10 RR 026825. Specimens were provided by the UC Davis Pathology Biorepository, funded by the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer and the UC Davis Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. The sequencing was carried out at the DNA Technologies and Expression Analysis Cores at the UC Davis Genome Center, supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Shared Instrumentation Grant 1S10OD010786-01.

Today, more than 80% of children diagnosed with cancer are alive 5 years after treatment. This is one of the biggest successes of pediatric medicine in the last 50 years. But the advances in treatment can have a cost: Some childhood cancer survivors develop life-threatening heart problems later in life, due in part to the chemotherapy that initially helped save them.

One of these heart-damaging drugs is doxorubicin (Adriamycin), which is used to treat many types of childhood and adult cancers. Results from a new study show that giving a drug called dexrazoxane (Zinecard) before each dose of doxorubicin substantially decreases the risk that childhood cancer survivors will have treatment-related heart problems in adulthood.

For younger patients, treatment-related heart damage is “an important, life-changing problem because it can impact many decades of life,” said one of the study leaders, Eric Chow, M.D., of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. The study’s findings, he added, have immediate implications for children and teens being treated for cancer today.

The study evaluated the cardiovascular health of 195 people who had been diagnosed with cancer in childhood, about half of whom had received dexrazoxane prior to doxorubicin in clinical trials years earlier.

Almost two decades after their cancer diagnosis, study participants who had received dexrazoxane had healthier hearts than participants who had not received it.

“This has potential to be practice changing,” Dr. Chow said, noting that some doctors have been hesitant to use dexrazoxane without more definitive evidence that it provides long-term protection against heart issues.

Findings from the NCI-funded study were published January 20 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“This is a very important study,” said pediatric oncologist Nita Seibel, M.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, who was not involved in the work. “We want to make sure childhood cancer survivors have the best quality of life … and anything we can do to prevent heart disease would be beneficial.”

Heart disease is one of the most concerning long-term side effects from doxorubicin therapy. At least 10% of people who receive high doses of the drug during treatment for childhood cancer experience heart failure by age 40.

Adults with cancer are also at risk of cardiac injury from doxorubicin. In 1995, dexrazoxane was approved by the Food and Drug Administration to reduce the risk of doxorubicin-induced heart damage in women being treated for breast cancer.

In the early 1990s, study co-leader Steven Lipshultz, M.D., chair of the Department of Pediatrics at the University at Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, spearheaded research showing that dexrazoxane could prevent short-term chemotherapy-induced heart damage in children with leukemia. But for years, the drug hasn’t been used widely in children being treated for cancer, Dr. Chow said, due to uncertainties about its long-term risks and benefits.

In the new study, dubbed HEART, participating hospitals in the United States and Canada recruited people who had been treated for childhood cancer at their institutions. The average age of people in the study was 29. All had participated in one of several NCI-supported Children’s Oncology Group or Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Childhood ALL Consortium clinical trials testing dexrazoxane almost 20 years earlier.

Clinicians from the hospitals where study participants were initially treated completed a one-time assessment of each participant’s heart health. That included measuring the structure and pumping strength of the heart’s left ventricle and screening for blood-based markers of heart damage and stress.

Compared with participants who had not received intravenous dexrazoxane prior to doxorubicin, those who received it had significantly better heart-pumping strength, without significant differences in the heart’s ventricular structure. They also had more normal markers of heart muscle stress.

The protection was most notable in those who had received a cumulative dose of doxorubicin greater than 250 mg/m2. This dose is considered to trigger a higher risk for heart disease, according to recently published international guidelines. Dr. Lipshultz emphasized, however, that any child treated with doxorubicin is likely at some risk for future heart problems, regardless of their cumulative dose.

“We found that, 18 years later, the protection to the heart was sustained,” Dr. Lipshultz said.

Importantly, he continued, the new results add to previously reported findings from the same study showing that giving dexrazoxane doesn’t make treatment with doxorubicin less effective against the cancer or increase the likelihood of survivors developing a second primary cancer—a concerning possibility proposed by some doctors.

This is “reassuring,” particularly to the families of children facing treatment with doxorubicin, Dr. Seibel said. “In the past, you would have to say that there is limited long-term data … [so] having longer-term data is definitely better.”

Doxorubicin is a type of anthracycline. This class of drugs includes many of the most effective chemotherapy drugs for childhood cancers—more than 50% of children with cancer are treated with an anthracycline. But these drugs also harm healthy cells, including heart muscle.

Dr. Lipshultz was one of the first cardiologists to recognize this problem. In the 1980s, he consulted on several cases of childhood cancer survivors who developed heart failure 10 or more years after their cancer diagnosis.

The prevailing thinking at the time was that children who didn’t show evidence of heart failure during treatment were unlikely to have future heart issues, he recalled. But after evaluating more than 100 survivors of childhood cancer who had been treated with doxorubicin, he discovered that more than 60% had unhealthy hearts. This percent, as well as the severity of heart problems for the group, increased over time.

“What we have shown in other studies is that damage occurs with even the very first dose of anthracyclines,” said Dr. Lipshultz, who believes the heart should be protected before every dose.

For 30 years, Dr. Lipshultz has argued that the treatment paradigm for children receiving doxorubicin as part of their cancer treatment needs to shift, noting that the successful treatment of childhood cancer should consider the quality of life for the cancer survivor and their family over a lifespan.

In that sense, these new findings are “so exciting,” Dr. Lipshultz said, because they show we can help prevent long-term damage to the heart from an anthracycline—an effective childhood cancer treatment with an unfortunate side effect.

When an anthracycline enters a cell, it binds to iron, he explained. This creates free radicals that “punch holes” in heart muscle cells and irreversibly damage mitochondria, the energy factories that allow the heart muscle to squeeze with good force, Dr. Lipshultz said. This cell death and mitochondrial damage in childhood leads to an adult heart with weaker muscles, which puts more stress on the heart.

Dexrazoxane, when administered immediately before each doxorubicin infusion, counters this effect by binding up iron in the blood, he continued. In the process, less iron is available to doxorubicin, which decreases the production of free radicals.

Dr. Chow noted that there are factors to consider when using dexrazoxane in children with cancer, such as the potential for a decrease in the production of blood cells in those who are already vulnerable to illness. However, “you can’t give dexrazoxane retroactively,” he said.

Recent guidelines from international organizations recommend dexrazoxane for children receiving certain doses of anthracyclines. Already in the United States, some upcoming treatment guidelines for specific cancers are going to recommend that dexrazoxane be given with any anthracycline dose, Dr. Seibel noted.

More work to be done

The study team acknowledged that the average age of the participants was only 29 years, and clinical heart failure following treatments for childhood cancer may not appear until later. It will be important to follow these patients to see if the lower risk of heart problems becomes more prominent over even longer periods, they wrote.

Dr. Chow noted that most childhood cancer survivors today didn’t receive dexrazoxane prior to their anthracycline treatments. “But rather than despair over that fact, the most important thing for those survivors is trying to control modifiable risk factors for heart disease,” he emphasized. That includes things like maintaining a healthy weight and blood pressure, and controlling diabetes and cholesterol levels.

For now, dexrazoxane is the only heart-protective drug available to children with cancer.

However, some groups are exploring additional protective measures, Dr. Chow said, such as testing a type of anthracycline that has a special fat coating to see if it can stop it from damaging the heart. Other researchers are trying to prevent heart damage by blocking proteins required for the death of heart cells.

Moving forward, this study shows the power of collaborative research involving both oncologists and cardiologists, Dr. Chow said. As a cardiologist, Dr. Lipshultz agreed, saying that he feels privileged to study this generation of long-term survivors of childhood cancer.

Source: National Cancer Institute

Explore other NCI Resources for Sarcomas

When you have cancer, your body needs proper nutrients and calories to recover from treatment. Yet, eating well can be difficult when you feel nauseous or don’t have the energy to cook. That’s where an oncology dietitian comes in.

An oncology dietitian (also called an oncology nutritionist) is a key member of your cancer care team. Typically, your oncologist will refer you to an oncology dietitian.

With their extensive background in nutrition, oncology dietitians help you create a meal plan that promotes healing and minimizes side effects while undergoing cancer treatment.

With the help of Melinda Pundt, RDN, LDN, senior dietician nutritionist at the Levine Cancer Institute, we provide more insight into what an oncology dietitian does and how they can support you on your journey to recovery.

An oncology dietitian works with cancer patients and their families to develop a diet during radiation.

This medical professional helps patients adjust their nutritional intake to optimize health and minimize side effects caused by cancer and cancer treatments.

After gathering more information, your oncology dietitian will develop a nutrition plan with specific food-related goals. This plan will likely include lots of fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins. But it may also include surprising foods like gravy or milkshakes.

Some of the food-related goals within a meal plan are specific to the patient.

For example, if you have experienced dramatic weight loss during chemotherapy, your goal may be to gain 20 pounds. To increase your body mass, your oncology dietitian may offer specific calorie and protein benchmarks.

Your oncology dietitian may also offer:

Good nutrition in cancer patients has been linked to better chances of recovery and lower incidences of remission.

A well-rounded diet can also:

“Your body is constantly having cells damaged from treatment and having cells repair

after treatments,” Pundt offers.

“A balanced diet helps provide your body with the vital vitamins, minerals, protein and energy to help it repair and heal after every treatment.”

Pundt says that creating a nutritional guide for cancer patients is a delicate balance.

Though the patient needs to consume a diet full of nutrient-dense foods, they also need to eat what tastes good to them.

“Overall, we want the majority of our diet to come from nutrient dense sources, including whole grains, lean protein, healthy fats, vegetables and fruits,” Pundt says.

“But this does not mean every single meal and snack has to be perfectly balanced. Our

comfort foods still provide us with nutrients and joy.”

Many cancer patients are intimidated by oncology nutritionists. They worry that the dietitian will be overly critical of their current diet or suggest they stop eating their favorite foods.

However, your oncology nutritionist is here to support you. Just like how you have a say in choosing your cancer treatment plan, you also have a say in what you eat.

“There are no bad or off-limit foods,” adds Pundt.

“During treatment, your body is using more energy than it would normally. The foods that bring you joy can help with getting in some extra nutrients to support your body during treatments so you can finish treatment on time.”

During your first consultation, your oncology nutritionist will perform a physical assessment. Since 85% percent of cancer patients experience malnutrition at some point during radiation treatment, your dietitian will look for fat and muscle loss, thinning hair, brittle nails, and other tell-tale signs of a nutritional imbalance.

The nutritionist will also ask you lots of questions about your diet, like:

“We like to get a feel for our patients’ baseline or normal diet. This can help us identify changes in their diet during treatment,” says Pundt.

“We also like to review any possible nutrition related side effects that patients may experience while undergoing treatment and address these as needed.”

To get the most out of your first dietitian consultation, Pundt suggests that patients:

Make a list of medications, supplements, and vitamins. If you can’t bring all of your bottles with you, take photos.

Note any side effects you are experiencing and when you experience them (e.g. nausea after eating breakfast). Your dietitian may be able to recommend certain foods that will ease symptoms.

Keep a food log for at least a week ahead of time. “Sometimes we aren’t eating as balanced as we may think,” says Pundt. “Food journaling can help you and your dietitian identify if there is anything missing in your diet.”

Any questions you may have. “We want you to be active and present in the management of your health and nutrition,” Pundt says.

During your first consultation, your oncology nutritionist will perform a physical assessment. Since 85% percent of cancer patients experience malnutrition at some point during radiation treatment, your dietitian will look for fat and muscle loss, thinning hair, brittle nails, and other tell-tale signs of a nutritional imbalance.

The nutritionist will also ask you lots of questions about your diet, like:

“We like to get a feel for our patients’ baseline or normal diet. This can help us identify changes in their diet during treatment,” says Pundt.

“We also like to review any possible nutrition related side effects that patients may experience while undergoing treatment and address these as needed.”

To get the most out of your first dietitian consultation, Pundt suggests that patients:

Make a list of medications, supplements, and vitamins. If you can’t bring all of your bottles with you, take photos.

Note any side effects you are experiencing and when you experience them (e.g. nausea after eating breakfast). Your dietitian may be able to recommend certain foods that will ease symptoms.

Keep a food log for at least a week ahead of time. “Sometimes we aren’t eating as balanced as we may think,” says Pundt. “Food journaling can help you and your dietitian identify if there is anything missing in your diet.”

Any questions you may have. “We want you to be active and present in the management of your health and nutrition,” Pundt says.

During your consultation, your oncology dietitian will also discuss food safety. Since cancer and cancer treatment can weaken your immune system, it’s important that you avoid food-borne illnesses like salmonella and norovirus.

“Food safety is especially important for those that may have a weakened immune system, like oncology patients. Certain cancer treatments can make it harder for your body to fight off infection so it is important to follow basic food safety rules to lower your risk of getting a food-borne illness,” offers Pundt.

To keep your food safe, your oncology dietitian will recommend:

Source: SERO

On December 9, 2022, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved atezolizumab (Tecentriq, Genentech, Inc.) for adult and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older with unresectable or metastatic alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS).

Efficacy was evaluated in Study ML39345 (NCT03141684), an open-label, single-arm study in 49 adult and pediatric patients with unresectable or metastatic ASPS. Eligible patients were required to have histologically or cytologically confirmed ASPS incurable by surgery and an ECOG performance status of ≤2. Patients were excluded for primary central nervous system (CNS) malignancy or symptomatic CNS metastases, clinically significant liver disease, or a history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, pneumonitis, organizing pneumonia, or active pneumonitis on imaging. Adult patients received 1200 mg intravenously and pediatric patients received 15 mg/kg (up to a maximum of 1200 mg) intravenously once every 21 days until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The main efficacy outcome measures were overall response rate (ORR) and duration of response (DOR) determined by an independent review committee using RECIST v1.1. ORR was 24% (95% CI: 13, 39). Of the 12 patients who experienced an objective response, 67% had a DOR of 6 months or more, and 42% had a DOR of 12 months or more.

The median patient age was 31 years (range: 12-70); 47 adult patients (2% were ≥65 years of age) and 2 pediatric patients ≥12 years of age were enrolled; 51% were female, 55% White, 29% Black or African American, 10% Asian.

The most common adverse reactions (≥15%) were musculoskeletal pain (67%); fatigue (55%); rash (47%); cough (45%); nausea, headache, and hypertension (43% each), vomiting (37%), constipation and dyspnea (33% each), dizziness and hemorrhage (29% each), insomnia and diarrhea (27% each), pyrexia, anxiety, abdominal pain and hypothyroidism (25% each), decreased appetite and arrhythmia (22% each), influenza-like illness and weight decreased (18% each), and allergic rhinitis and weight increased (16% each).

The recommended atezolizumab dosage for adult patients is 840 mg every 2 weeks, 1200 mg every 3 weeks, or 1680 mg every 4 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The recommended dosage for pediatric patients 2 years of age and older is 15 mg/kg (up to a maximum of 1200 mg) every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

View full prescribing information for Tecentriq.

This review used the Assessment Aid, a voluntary submission from the applicant to facilitate the FDA’s assessment. The FDA approved this application 3 weeks ahead of the FDA goal date.

This application was granted priority review and breakthrough designation. A description of FDA expedited programs is in the Guidance for Industry: Expedited Programs for Serious Conditions-Drugs and Biologics. The application also was granted orphan drug designation.

Healthcare professionals should report all serious adverse events suspected to be associated with the use of any medicine and device to FDA’s MedWatch Reporting System or by calling 1-800-FDA-1088.

For assistance with single-patient INDs for investigational oncology products, healthcare professionals may contact OCE’s Project Facilitate at 240-402-0004 or email OncProjectFacilitate@fda.hhs.gov.

Source: FDA

“2022 was an outstanding year for our foundation!” said Susan Udelson, Executive Director. “During our signature fundraiser, The Sarcoma Stomp, presented by AmWINS, dedicated fundraisers and donors fired on all cylinders, and companies supported in droves. We held Golf Fore Sarcoma in the fall and gained many new and generous supporters. We also had the great fortune of benefiting from several other fundraisers this year: All-In to Fight Cancer’s Texas Hold’em tournament, Food & Beverage Social Club’s FORK Cancer chef’s dinner, and the Bakerstrong golf tournament in memory of Clayton Baker, hosted by his friends and Ernst & Young colleagues. We are extremely grateful to these partners who helped us amplify our impact.”

On December 6, 2022 the Paula Takacs Foundation for Sarcoma Research held a Gift Presentation and Reception for Levine Cancer Institute, Levine Children’s Hospital and other guests. It was sponsored by and held at Loretta’s Restaurant in Charlotte, NC. We thank Loretta’s Restaurant for supporting our mission!

The Paula Takacs Foundation donors have funded a pilot study of a sarcoma-specific blood biopsy technique developed by Levine Cancer Institute. Researchers now report that the preliminary data is extremely encouraging! This study has found evidence of circulating tumor DNA of several sarcoma subtypes in the blood. This has the potential to be a game changer for more effective patient management and a better understanding of sarcoma drivers.

Donations have also supported Levine researchers in the study of genomic sequencing of over 70 synovial sarcoma specimens and comparing to patient outcomes. Although not yet published, this is currently the largest study of synovial sarcoma in the world! It is very significant to amass a large study in a very rare disease. It helps researchers uncover the drivers of this disease and gives patients so much hope for a cure.

Read about all the studies your dollars fund.

The Foundation is also proud to announce a new initiative. Through the Growing Hope Through Art program, a fundraising arm the Paula Takacs Foundation, we will knit together our community in awareness and purpose about sarcomas. Powerful art installations commissioned by the Program will stand as a symbol of our commitment to funding local research, and amplifying awareness as they tell stories of hope throughout the Charlotte region. The first installation, by glass artist Jake Pfeifer of Hot Glass Alley, will be in a prominent corridor at Levine Cancer Institute. Seasons of Life, a hand-blown glass tree with a seasonal cadence of blossoms, will symbolize the courageous sarcoma journey of the artist, and will pay homage to all cancer patients and their healthcare heroes.

To learn more, visit growinghopethroughart.org.

There are many ways to get involved in the work of the Paula Takacs Foundation! To learn more, you can visit our website, follow us on Instagram and Facebook, and opt in to our periodic email updates. We need YOU to help fund the research that can lead to cures, and to spread awareness that can lead to faster diagnoses in order to save more lives!

Subscribe to our mailing list HERE and receive our newsletters.

Clinical trials are an indispensable step in moving new cancer treatments from laboratory discoveries into everyday patient care. The initial human studies of new cancer treatments are called phase 1 clinical trials, and their primary goal is to find a safe dose for further testing. But a recent analysis shows that, despite their focus on safety, phase 1 trials of new cancer treatments may benefit participants more than previously thought.

In the analysis, Naoko Takebe, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP), and her NCI colleagues surveyed the last two decades of phase 1 clinical trials for solid tumors sponsored by CTEP. Over that period, they found, the number of trial participants whose tumors shrank or disappeared nearly doubled and the percentage of patients whose tumors stopped growing for a time also increased. The risk of death caused by a new treatment being tested, however, remained steady and very low, at less than 1%.

In this interview, Dr. Takebe talks about the findings and how they may alter the perception of these important early-phase trials.

Yes, the perception of the potential benefit to patients hasn’t caught up with modern drug development. In the past, participants in phase 1 trials generally have had low tumor response rates, about 4%–5%. In addition, the primary purpose of phase 1 trials is to assess safety. So, some doctors have not been enthusiastic about referring patients to phase 1 trials.

People also have to go through the standard treatment options first, and usually only those patients who run out of those options, or are not able to receive those standard options for some reason, are eligible to participate in a phase 1 trial. So there have been concerns about including people with advanced cancer, who may be very ill, in early clinical trials.

But we and others have now shown that things have changed. Participating in phase 1 trials has more potential for clinical benefit than is commonly believed, largely due to the development of modern cancer drugs, like targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and new combination therapies.

So I hope this analysis will have a positive impact on the enrollment of patients into phase 1 trials by doctors, who may feel more comfortable referring patients.

No, they can definitely still participate, as long as they meet all the criteria for participation in a trial, and their doctor agrees it’s safe. And we have to overcome the misperception that they can’t.

In addition to the newer types of drugs being developed, we’ve also had advancements in supportive care. In all clinical trials, we’re now much more proactive in supporting patients, including providing pain control and palliative care services, and watching for and appropriately managing side effects.

So factors like age should not necessarily stop patients from participating in a phase 1 clinical trial. But they should serve as an alert for the clinical trial team to be aware, to make sure patients understand the risks, and to monitor older, sicker patients more closely.

Participation in phase 1 trials does pose both a time and logistical burden, because there are frequent safety assessments on top of other aspects of treatment. Some patients may want more time at home with their families, rather than going back and forth between appointments.

But in order for patients to make an informed decision, we believe those with no further standard treatment options for their cancer should be informed about the option of participating in phase 1 trials.

Trials testing the safety and tolerability of a new drug for the first time in people are mostly sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. NCI sponsors some first-in-human phase 1 trials, but they’re not that common.

NCI tends to sponsor phase 1 trials investigating new combinations of drugs. Even if the drugs being used together have been tested individually in people, they are also required to be tested together in a phase 1 trial to determine the optimal dose of each agent that can be given safely in combination.

About 70% of the clinical trials that we analyzed in this study were drug combination trials.

Enrollment in phase 1 trials has tended to be very slow. If we can enroll more patients more quickly, we can do additional phase 1 studies and ultimately bring more new drugs to patients faster.

But for more referrals, we hope oncologists will view these recent findings as paradigm shifting, and to have discussions with their patients about the potential benefit of participating in a phase 1 clinical trial, alongside the opportunity to advance cancer research.

The patients ultimately decide whether they should participate, but we, the oncologists, have to give them that option.

Source: National Cancer Institute, Cancer Currents Blog

Photo Credit: iStock

If you are thinking about joining a clinical trial as a treatment option, the best place to start is to talk with your doctor or another member of your health care team. Often, your doctor may know about a clinical trial that could be a good option for you. He or she may also be able to search for a trial for you, provide information, and answer questions to help you decide about joining a clinical trial.

Some doctors may not be aware of clinical trials that could be appropriate for you. If so, you may want to get a second opinion about your treatment options, including taking part in a clinical trial.

If you decide to look for trials on your own, the steps discussed here can guide you in your search. The NCI‘s Cancer Information Service can also provide a tailored clinical trials search that you can discuss with your doctor. To reach them call 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237) and select option 2. This is a free service. Keep in mind that the search results do not replace advice from your doctor.

If you decide to look for a clinical trial, you will need to know certain details about your cancer diagnosis and compare these details with the eligibility criteria of any trial that interests you. Eligibility criteria are the requirements that must be met for you to join a clinical trial.

Examples of eligibility criteria include

To help you gather details about your cancer, complete as much of the Cancer Details Checklist as possible. Refer to the form during your search for a clinical trial.

If you need help filling out the form, talk with your doctor or nurse or social worker at your doctor’s office. The more information you can gather, the easier it will be to find a clinical trial to fit your situation.

There are many lists of cancer clinical trials taking place in the United States. Some trials are funded by nonprofit organizations, including the U.S. government. Others are funded by for-profit groups, such as drug companies. Hospitals and academic medical centers also sponsor trials conducted by their own researchers. Because of the many types of sponsors, no single list contains every clinical trial.

Helpful tip: Whichever website you use to search for clinical trials, be sure to bookmark or print a copy of the protocol summary for every trial that interests you.

A protocol summary should explain the goal of the trial and describe which treatments will be tested. It should also list the locations where the trial is taking place.

Keep in mind that protocol summaries are written for health care providers and use medical language to describe the trial that may be difficult to understand. For help understanding the protocol summary, call, email, or chat with one of our cancer information specialists.

NCI’s website helps you find NCI-supported clinical trials that are taking place across the United States, Canada, and internationally. The list includes

If you need help with your search, you can call, email, or chat with one of our trained information specialists. They will need to know details about your cancer, so have your Cancer Details Checklist ready.

In addition to NCI‘s list of cancer clinical trials, you may want to check a few other lists.

ClinicalTrials.gov

ClinicalTrials.gov, which is part of the National Library of Medicine, lists clinical trials for cancer and many other diseases and conditions. It contains trials that are on NCI’s list of cancer trials as well as trials sponsored by pharmaceutical or biotech companies that may not be on NCI’s list.

Cancer centers and clinics that conduct cancer clinical trials

Many cancer centers across the United States, including NCI-Designated Cancer Centers, sponsor or take part in cancer clinical trials. The websites of these centers usually have a list of the clinical trials taking place at their institutions. Some of the trials included in these lists may not be on NCI’s list.

Keep in mind that the amount of information about clinical trials on these websites can vary. You may have to contact a cancer center clinical trials office to get more information about the trials that interest you.

Drug and biotechnology companies

Many companies provide lists of the clinical trials that they sponsor on their websites. Sometimes, a company’s website may refer you to the website of another organization that helps the company find patients for its trials. The other organization may be paid fees for this service.

Clinical trial listing services

Some organizations provide lists of clinical trials as a part of their business. These organizations generally do not sponsor or take part in clinical trials. Some of them may receive fees from drug or biotechnology companies for listing their trials or helping find patients for their trials.

Keep the following points in mind about clinical trial listing services

Cancer advocacy groups

Cancer advocacy groups provide education, support, financial assistance, and advocacy to help patients and families who are dealing with cancer, its treatment, and survivorship. These organizations recognize that clinical trials are important to improving cancer care. They work to educate and empower people to find information and obtain access to appropriate treatment.

Advocacy groups work hard to know about the latest advances in cancer research. Some will have information about clinical trials that are enrolling patients.

To find trials, search the websites of advocacy groups for specific types of cancer. Many of these websites have lists of clinical trials or refer you to the websites of organizations that match patients to trials. Or, you can contact an advocacy group directly for help finding clinical trials.

Once you have completed the Cancer Details Checklist and found some trials that interest you

Helpful tip: Don’t worry if you can’t answer all of the questions below just yet. The idea is to narrow your list of potential trials, if possible. However, don’t give up on trials you’re not sure about. You may want to talk with your doctor or another health care team member during this process, especially if you find the protocol summaries hard to understand.

Trial objective

What is the main purpose of the trial? Is it to cure your cancer? To slow its growth or spread? To lessen the severity of cancer symptoms or the side effects of treatment? To determine whether a new treatment is safe and well-tolerated? Read this information carefully to learn whether the trial’s main objective matches your goals for treatment.

Eligibility criteria

Do the details of your cancer diagnosis and your current overall state of health match the trial’s eligibility criteria? Some treatment trials will not accept people who have already been treated for their cancer. Other treatment trials are looking for people who have already been treated for their cancer.

Helpful tip: If you have just found out that you have cancer, the time to think about joining a trial is before you have any treatment. Talk with your doctor about how quickly you need to make a treatment decision.

Trial location

Is the location of the trial manageable for you? Some trials take place at more than one location. Look carefully at how often you will need to receive treatment during the course of the trial. Decide how far and how often you are willing to travel. You will also need to ask whether the sponsoring organization will pay for some or all of your travel costs.

Study length

How long will the trial run? Not all protocol summaries provide this information. If they do, consider the time involved and whether it will work for you and your family.

After thinking about these questions, if you are still interested in a clinical trial, then you are ready to contact the team running the trial.

There are a few ways to reach the clinical trial team.

Whether you or someone from your health care team speaks with the clinical trial team, this is the time to get answers to questions that will help you decide whether or not to take part in this particular clinical trial. Questions to Ask Your Doctor about Treatment Clinical Trials can help you think about questions you want to ask.

Remember to keep your Cancer Details Checklist handy to help you answer some of the questions that may be asked.

To make a final decision, you will want to know the potential risks and benefits of all treatment options available to you. If you have any remaining questions or concerns, you should discuss them with your doctor. Ask your doctor some of the same questions that you asked the trial coordinator. You should also ask your doctor about the risks and benefits of standard treatment for your cancer. Then, you and your doctor can compare the risks and benefits of standard treatment with those of treatment in a clinical trial. You may decide that joining a trial is your best option, or you may decide not to join a trial. It’s your choice.

If you decide to join a clinical trial for which you are eligible, schedule a visit with the team running the trial.

Source: National Cancer Institute

Will a specific cancer treatment actually work for a person diagnosed with cancer? Every person’s cancer is different, and even when a tumor has a genetic change for which there’s a matching targeted therapy, there’s no guarantee a given treatment is going to work.

But based on the results of a small study, funded in part by NCI, a team of researchers hopes to soon offer oncologists a new tool to guide treatment choices for their patients.

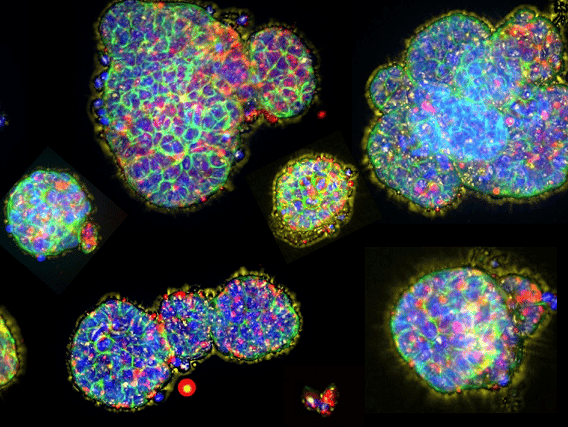

The tool is a new type of personalized tumor model, called micro-organospheres. And in a small study of eight people with advanced colorectal cancer, the researchers used the model to accurately predict whether the chemotherapy drug oxaliplatin would shrink their tumors.

Results from the study, led by Xiling Shen, Ph.D., the CEO of the biotechnology company Xilis, were reported June 2 in Cell Stem Cell.

To create the micro-organospheres, the research team takes tissue from a patient’s tumor biopsy and runs it through a desktop device, about the size of a standard printer. The end product: thousands of three-dimensional mini-replicas of the cancer suspended in tiny compartments on a lab dish.

Creating the models required much less tumor tissue than is usually required to grow other cancer models that use a patient’s own tumor tissue, Dr. Shen and his colleagues reported. And they were created quickly, in less than 2 weeks. That is much faster than similar models can be created, explained one of the study’s leaders, David Hsu, M.D., Ph.D., of the Duke Cancer Institute.

Their analyses also showed that the micro-organospheres largely retained the molecular features of the tumors from which they were created. And the models had many other components of the tumor’s surroundings, including immune cells and structural cells. The makeup of this tumor “microenvironment,” as it’s called, can influence how tumors respond to treatment.

The micro-organospheres “overcome a lot of the barriers” that have prevented similar tumor models from being used to help direct everyday patient care, Dr. Hsu said.

A larger study is being launched to determine whether these early findings hold up. Dr. Shen and Dr. Hsu, along with a third member of the team, Hans Clevers, M.D., Ph.D., of the pharmaceutical company Roche and a pioneer in organoid technology, jointly founded Xilis in 2019 to commercialize the technology.

The findings from this first study “are just a proof of concept,” Dr. Hsu acknowledged. “We need a larger study to … have the data needed to say if [these models] precisely capture patients’ response to treatment.”

Cancer models, including tumor cell lines and animal models, are widely used research tools. They usually serve as generalized stand-ins for a specific type or form of cancer.

But over the past decade, researchers have taken these representations of cancer to the next level, developing personalized models created from individual patients’ tumor tissue. Efforts to create these patient-derived tumor models, as they’re called, are considered to be an important part of a concept known as precision oncology: treating a patient’s cancer based on its unique clinical and molecular features.

The two most common patient-derived models are mouse models called patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) and tumor-like cell clusters called organoids that are grown in lab dishes.

Because they grow as human tumors in living tissue, there was initially great hope that PDXs might be used to direct care for individual patients, explained Konstantin Salnikow, Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Biology and who oversees NCI’s Patient-Derived Models of Cancer program.

But it soon became clear that because of certain limitations, in their current forms, PDX models may primarily be most useful as research tools and not to help direct the care of individual patients, Dr. Salnikow said.

Those limitations include the time it takes to establish them—a minimum of several months, and “sometimes up to a year,” Dr. Salnikow said. And because PDX mice lack functioning immune systems, he added, they can’t capture the important interactions between immune cells and tumors, which can influence how cancer treatments work.

Organoids, which are created using specific types of stem cells in tumor tissue, are grown in laboratory dishes. These models can be created somewhat more quickly and inexpensively than PDX models.

But when it comes to cancer, treatment typically needs to begin quickly after diagnosis, usually within a few weeks, said Dr. Hsu, who specializes in treating colorectal cancer.

Not only does creating organoids require a relatively large amount of tumor tissue—which isn’t always easy to come by—it also can take several months. In addition, the number of organoids produced is relatively small. For the time being, these factors may limit their potential for use in everyday patient care, he explained.

Micro-organospheres are intended to address both models’ limitations.

An electrical engineer by training, Dr. Shen developed the system for creating micro-organospheres at Duke. He recently left the university to lead Xilis full time.

The system’s lynchpin is a technology called microfluidics, which allows for precise handling of very small amounts of material suspended in specialized liquids. Producing the micro-organospheres also involves growing the collected cells in oil-based droplets, which required the researchers to develop a way to then remove the oil without harming the cells.

The entire process is highly automated and takes place in a small, desktop device. By automating production, the system eliminates much of the variability involved in growing organoids, which requires multiple manual steps, and streamlines the entire process, Dr. Shen explained.

As a result, he continued, there won’t be “different results depending on who cultured [the] cells.”

And rather than a just few organoids or PDXs, the product that emerges from the system is “thousands of miniaturized tumors,” Dr. Shen said, “and those mini-tumors are ready for drug testing within days.”

Source: National Cancer Institute

Photo Credit: Image used courtesy of Xiling Shen

The Cancer Grand Challenges program will award $100 million to four interdisciplinary teams from around the world to solve some of the toughest challenges in cancer research. Each team will receive $25 million over five years. The teams were announced at the Cancer Grand Challenges Summit on June 16, 2022, in Washington, D.C.

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Cancer Research UK, the world’s leading funders of cancer research, partnered to launch the Cancer Grand Challenges program. Cancer Grand Challenges aims to provide multiple rounds of funding for interdisciplinary research teams from around the world whose novel ideas have the greatest potential to advance cancer research and improve outcomes for people affected by cancer.

The research being conducted by the four selected interdisciplinary teams includes investigation of 1) a muscle-wasting condition in cancer patients known as cachexia, 2) the biology of extrachromosomal DNA in cancer 3) new therapies for solid tumors in children, and 4) what triggers normal cells harboring cancer-causing mutations to become tumor cells.

“The partnership with Cancer Research UK to develop the projects funded for the Cancer Grand Challenges program will enable a global collaboration on a disease that has touched everyone around the world,” said Douglas R. Lowy, M.D., acting director of NCI. “We’re confident these multidisciplinary teams of scientists — with the flexibility and scale to innovate and carry out cutting-edge research — will be able to address several critical cancer research problems that can advance the understanding of cancer and benefit patients.”

“Cancer is a global issue that demands global collaboration. By investing in team science at this scale, we will bring new thinking to problems that have, for too long, stood in the way of progress,” said David Scott, Ph.D., director of Cancer Grand Challenges, Cancer Research UK. “At its core, Cancer Grand Challenges provides multidisciplinary teams the time, space, and freedom to innovate and drive progress against cancer that the world urgently needs. The new teams join a growing global community already making major discoveries, including unlocking new information about the tumor microenvironment and transforming our understanding of the early stages of disease development.”

A total of 169 research teams from more than 60 countries submitted preliminary proposals outlining how they would tackle one of the nine challenges posed by the Cancer Grand Challenges program. From those submissions, 11 teams were chosen by an expert group — which included input from a patient committee — to receive seed funding to develop their ideas into full proposals. Four funded teams, representing four of the challenges, were selected from those proposals.

“Through this unique partnership, Cancer Grand Challenges fosters scientific creativity of the highest order, giving priority to innovative ideas that are beyond what can be supported through more traditional mechanisms,” said Dinah S. Singer, Ph.D., NCI deputy director for scientific strategy and development.

The next funding rounds of the NCI-Cancer Research UK partnership are planned for 2023 and 2025. For more information about the Cancer Grand Challenges program, visit https://www.cancer.gov/cancer-grand-challenges.

About the National Cancer Institute (NCI): NCI leads the National Cancer Program and NIH’s efforts to dramatically reduce the prevalence of cancer and improve the lives of cancer patients and their families, through research into prevention and cancer biology, the development of new interventions, and the training and mentoring of new researchers. For more information about cancer, please visit the NCI website at or call NCI’s contact center, the Cancer Information Service, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation’s medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit nih.gov.

Breakthrough findings were presented at the 2022 ASCO Annual Meeting and published in The New England Journal of Medicine today by researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) confirming a clinical complete response in all 14 patients who received the immunotherapy treatment dostarlimab as a first-line treatment for mismatch repair-deficient (MMRd) locally advanced rectal cancer. This new approach of “immunoablative” therapy uses immunotherapy to replace surgery, chemotherapy and radiation to remove cancer.

MSK’s Andrea Cercek, MD, Section Head of Colorectal Cancer and Co-Director of the Center for Young Onset Colorectal and Gastrointestinal Cancer, and Luis Alberto Diaz, Jr., MD, Head of the Division of Solid Tumor Oncology, led this groundbreaking clinical trial — which saw a 100% complete response rate among its patients. The study also provides a framework for evaluation of highly active therapies in the neoadjuvant setting, where patients are spared from chemoradiation and surgery while treating the tumor when it is most likely to respond.